Silverberry

This shrub is Elaeagnus commutata, and is also referred to as Wolfberry, or Wolf Willow.

This is not to be confused with Goji, which is also referred to as Wolfberry.

This is also not to be confused with Autumn Olive, which is also known as Silverberry.

They are entirely different plants and look completely different.

Now that we are all thoroughly confused, lets continue :-)

This is also not to be confused with Autumn Olive, which is also known as Silverberry.

They are entirely different plants and look completely different.

Now that we are all thoroughly confused, lets continue :-)

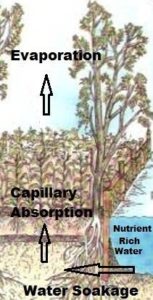

A close relative to Russian Olive, this particular shrub is a native of Canada, and is a valuable Nitrogen fixer in the boreal forest.

People typically place this plant in their yard as an ornamental feature, but it can be much more than a pretty face when put to work.

This shrub flowers in late May and provides hungry bees with an much needed source of food.

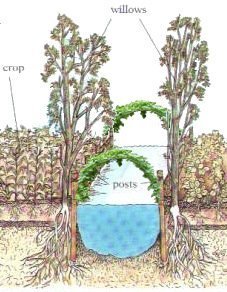

Growing to around 10 ft tall with a dense, thick foliage, Silverberry makes an excellent under story support species that can be used extensively as windbreaks, hedges, and chop n drop mulch, due to it's vigorous growth and coppicing ability. The bark is also a source of fibre for making rope and weaving baskets.

The wood itself produces an unpleasant smell when burned. This would probably be eliminated in rocket stoves, and mass heaters due to their high internal operating temperatures. However, there is little information about its suitability as a firewood due to this undesirable characteristic.

It produces a rather unattractive, yet edible fruit that can be used to make jelly. I have no idea what it looks and tastes like, so it might be more in the "survival food" category of value added products.

What is interesting with Silverberry, apart from what I've already written, is that fact that it is thorn less. Finally, a nitrogen fixing tree that doesn't require gloves to prune!

Widely considered as invasive, a permaculturist can put this plant to good use in a managed forest system. Furthermore, this plant does not tolerate shade, and will naturally die off as the primary tree species grow and the forest canopy develops. The very attributes that demonise this plant in the eyes of traditional agriculturists are essential in a regenerating forest ecosystem.

It provides shelter and nutrients for the mature forest as it grows, and then gracefully steps aside at the appropriate time. It really is a rather polite plant.

The wood itself produces an unpleasant smell when burned. This would probably be eliminated in rocket stoves, and mass heaters due to their high internal operating temperatures. However, there is little information about its suitability as a firewood due to this undesirable characteristic.

It produces a rather unattractive, yet edible fruit that can be used to make jelly. I have no idea what it looks and tastes like, so it might be more in the "survival food" category of value added products.

What is interesting with Silverberry, apart from what I've already written, is that fact that it is thorn less. Finally, a nitrogen fixing tree that doesn't require gloves to prune!

Widely considered as invasive, a permaculturist can put this plant to good use in a managed forest system. Furthermore, this plant does not tolerate shade, and will naturally die off as the primary tree species grow and the forest canopy develops. The very attributes that demonise this plant in the eyes of traditional agriculturists are essential in a regenerating forest ecosystem.

It provides shelter and nutrients for the mature forest as it grows, and then gracefully steps aside at the appropriate time. It really is a rather polite plant.

.ashx?h=800&la=en-AU&w=800)